The monarch butterfly is reddish-orange with black vein-like markings. There is a black border around its wings with white spots on it. Its wings look like stained glass windows. When its wings are open, they are about 3.5–4 inches (8.9–10.2 cm) wide.

Males and females are similar in appearance, but the black veins are thicker on the female’s wings, and the male has small pouches on its hind wings where it stores pheromones. Pheromones are special chemicals made and released by animals to communicate with other animals.

The bright orange of the monarch is a type of advertising coloration that warns predators away.

In the spring and summer, the monarch butterfly’s habitat is open fields and meadows with milkweed. In winter, it is found on the coast of southern California and at high altitudes in central Mexico.

Monarch butterfly larvae feed on milkweed. Adults gather nectar from flowers. The monarch is not a very pleasant meal for predators.

Eating milkweed causes the monarch to store alkaloids. Alkaloids are natural chemicals made by some plants that often taste bitter. This makes the monarch taste horrible to predators.

This is such an effective protection from predators; the viceroy butterfly has adapted to look like the monarch, so predators will leave it alone, too.

Monarch butterfly reproduction is a complicated process. It is tied to the migratory patterns of the monarch. In the monarch’s summer territory, which includes most of North America, monarchs will mate up to seven times. Each butterfly lives from 2-6 weeks. The male courts the female in the air. He then tackles her and mates with her on the ground.

As the monarchs migrate to their summer territory, the female lays her eggs on milkweed plants. The eggs take 3-15 days to hatch into larvae. The larvae feed on the milkweed for about two weeks. At the end of the two weeks, they attach themselves to a twig, shed their outer skin, and change into a chrysalis. This happens in just a few hours. In two weeks, a full-grown monarch emerges.

As fall approaches, non-reproductive monarchs are born. These are the butterflies that will migrate south. They will not reproduce until the following spring. These late-summer monarchs travel hundreds and even thousands of miles to their winter grounds in Mexico and California. These monarchs need a lot of energy to make their trip. They store fat in their abdomens, which helps them make the long trip south and survive the winter. During their five months in Mexico from November to May, monarchs remain mostly inactive. They remain perfectly still hour after hour and day after day. They live off the stored fat they gained during their fall migration.

When they first arrive at their winter locations in November, monarchs gather into clusters in the trees. By December and January, when the weather is at its coldest, the monarchs are tightly packed into dense clusters of hundreds or even thousands of butterflies. By mid-February, these clusters of butterflies begin to break up, and the monarchs begin to gather nectar. In the spring, they reproduce, and their offspring make the return trip to the north.

The monarch butterfly is a long-distance migrator. It migrates both north and south just like many birds do. But, unlike birds, individual butterflies don’t complete migration both ways. It is their great-grandchildren that end up back at the starting point.

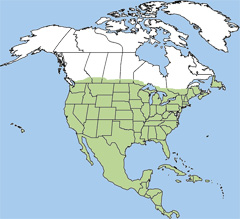

In the fall, monarchs in the north gather and begin to move south. In North America, two large population groups follow separate migration paths. Most monarchs east of the Rocky Mountains overwinter in the Sierra Madre Mountains in central Mexico, where they live in fir forests at high altitudes. Far western populations of monarchs winter along the coast of southern California, where they live in groves of pine, cypress, and eucalyptus trees. In the spring, they head north and breed along the way.

Monarch migration back to the north is like a relay race. The original butterfly dies along the way, but the offspring it leaves behind continues to the north, where the cycle starts again in the fall. There are populations of monarchs in California, Florida, and Texas that don’t migrate.

Monarch butterfly populations have declined by 84% in the U.S. due to habitat loss, climate change, loss of milkweed plants, pesticides, and disease.

You can help the butterfly by planting and not cutting down milkweed plants.

Support for NatureWorks Redesign is provided by:

Monarch butterflies can be seen in New Hampshire in the summer and the fall.

The monarch butterfly is found in North America from southern Canada south to South America and the Caribbean. It is most common east of the Rocky Mountains and is not found in some areas of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

Monarchs that live east of the Rocky Mountains usually overwinter in Mexico. Monarchs that live east of the Rocky Mountains may overwinter or live year-round in southern California.

The monarch butterfly has also been established in Hawaii and Australia.

NHPBS inspires one million Granite Staters each month with engaging and trusted local and national programs on-air, online, in classrooms and in communities.